The Proxy Playbook: Building Fast, Secure Middle Layers in Go

You’re in the middle of a Teams call with your DevOps crew when a service starts throwing alerts.

Requests are piling up, some users are getting errors, and the backend logs look like they’ve been hit by a firehose.

You could spin up more servers, but that’s just throwing hardware at the problem.

This is where proxies earn their keep.

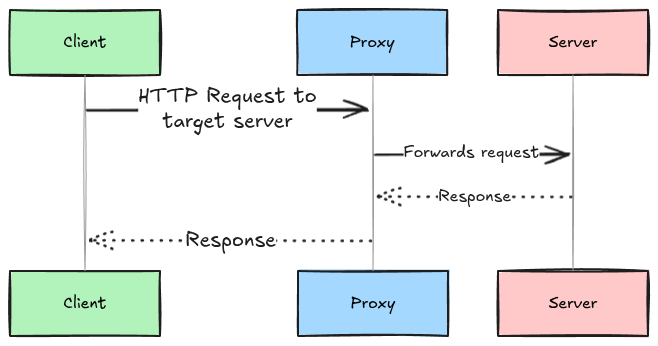

A proxy sits between the client and the server.

Instead of the client talking directly to the server, the request goes to the proxy first.

The proxy decides what to do, forward it, block it, cache it, or even route it somewhere else entirely and then sends the response back to the client.

Sometimes the proxy works for the client.

That’s a forward proxy, which hides the client’s identity and controls outbound requests.

Other times it works for the server.

That’s a reverse proxy, which hides the backend and controls inbound requests.

Forward proxy:

Used by clients (like browsers, apps, or an office network) to reach external servers.

It can filter requests, add anonymity, and cache responses so they don’t hit the internet every time.

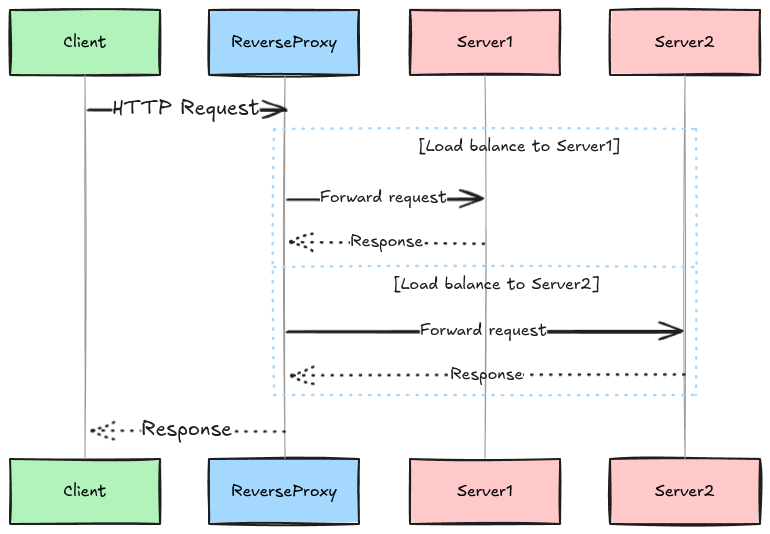

Reverse proxy:

Sits in front of your backend services, taking all incoming traffic.

It can load-balance across instances, terminate TLS, cache frequently requested data, and act as a shield against bad actors.

Why you’d actually use a proxy

Proxies aren’t just about hiding IP addresses.

In real systems, they’re the glue that makes things scale and stay secure:

- Load balancing – Spread requests across multiple servers so none get overloaded.

Some proxies also check server health and avoid sending traffic to a dead instance. - Caching – Store static files, API responses, or even entire pages so clients get faster results without hitting your app.

- Security – Keep backend IPs private, drop suspicious traffic before it touches your code, and handle TLS termination so your services don’t have to.

- Authentication – Make sure requests are legit before they hit your app. API gateways do this all the time with JWTs or API keys.

- Logging and monitoring – Since all traffic flows through it, a proxy is the perfect choke point to collect metrics, trace requests, and enforce rate limits.

- Privacy & Anonymity: Forward proxies can hide client IPs from destination servers. By replacing the client’s IP with the proxy’s IP, a proxy can prevent tracking of the original client and enable bypassing of geo-blocks. (This is why public proxies or Tor are used for privacy.)

All of these uses make proxies powerful.

However, proxies also introduce trade-offs. They become additional network hops and potential bottlenecks.

The catch with proxies

While proxies add features, they also have costs and limits:

- Extra latency – Every request takes a detour through the proxy. If it’s doing heavy inspection or encryption work, you’ll feel it.

- Single point of failure – If the proxy goes down and you don’t have a backup, your whole system is toast. Always run them in clusters with failover.

- Protocol limitations – Not every proxy speaks every protocol. Some might choke on HTTP/2, WebSockets, or anything non-HTTP unless you set them up for it.

- More moving parts – Proxies need maintenance, config tuning, cert updates, and the occasional debugging session from hell when a request disappears in the middle.

- Security isn’t automatic – Just because you’re using a proxy doesn’t mean your traffic is safe. If you don’t run TLS end-to-end or trust the wrong proxy, you might be leaking data.

Proxies in Microservices and Cloud

In modern cloud and microservices architectures, proxies are everywhere:

- API Gateways / Ingress: Tools like Kong, Traefik, or an NGINX Ingress controller act as reverse proxies (often with authentication, rate limiting, and TLS termination) in front of microservices.

They expose a unified HTTP endpoint to clients while routing internally based on hostname or path. - Service Mesh Sidecars: Technologies like Linkerd, or Consul use lightweight proxies injected beside each microservice.

Each service’s traffic is transparently intercepted by its sidecar proxy, which handles service-to-service load balancing, retries, monitoring, and mTLS encryption.

This means security policies (e.g. RBAC, quotas) are enforced at the proxy layer rather than in application code.

The service mesh treats these sidecars as network infrastructure for the microservices, automatically managing complex concerns like encrypted service-to-service calls. - Cloud CDN & Edge Proxies: Large cloud providers and CDNs (like Cloudflare or Amazon CloudFront) use distributed reverse proxies at the edge to cache content globally, protect against attacks, and accelerate delivery to end-users.

- Debugging and Testing: Developers often use forward proxies (like Charles Proxy, Fiddler, or mitmproxy) to capture and modify HTTP traffic for debugging or testing purposes.

In all of these scenarios, the proxy centralizes cross-cutting concerns (security, logging, caching) so services can focus on core logic.

Implementing a Reverse Proxy in Go

Go’s standard library makes writing a reverse proxy very simple.

This shows a reverse proxy, commonly used in microservices. The client thinks it’s talking to the server, but it’s actually talking to the reverse proxy, which decides which backend service to forward the request to.

The net/http/httputil package provides a ReverseProxy type. For example, to proxy all incoming requests to a target server, you can do:

targetURL, _ := url.Parse("https://example.com")

proxy := httputil.NewSingleHostReverseProxy(targetURL)

http.HandleFunc("/", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

log.Println("Proxying request:", r.URL.Path)

proxy.ServeHTTP(w, r)

})

log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil))

This handful of lines sets up a Go HTTP server on port 8080 that forwards every request to example.com.

Under the hood, httputil.NewSingleHostReverseProxy creates a handler whose ServeHTTP method rewrites the request’s URL and Host and then performs the request to the target, streaming the response back.

You can modify the ReverseProxy for advanced use: for instance, you can set proxy.ModifyResponse to change the response before it returns to the client, or provide a custom proxy.ErrorHandler to handle backend errors.

Importantly, Go’s ReverseProxy also handles HTTP protocol quirks: it will automatically use Connection: Upgrade headers if needed (enabling WebSocket tunneling) and passes through most headers correctly.

Using Go’s reverse proxy handler is both powerful and efficient.

It supports HTTP/2 out of the box (if the Go Transport does), it streams data without buffering the whole payload, and it reuses connections via the default http.Transport.

Many production proxies (in custom tools or frameworks) simply wrap this handler and add a few lines of logic.

Implementing a Forward Proxy in Go

Writing a forward proxy (where the client decides where to go) is a bit more involved, but still quite feasible in Go.

The main difference is that clients send requests with an absolute URL when using a forward proxy (e.g. GET http://api.example.com/data HTTP/1.1 instead of a relative path).

Image below shows a forward proxy, where the client explicitly connects to the proxy to reach the server. The server doesn’t know the client’s real IP — it only sees the proxy.

A Go proxy handler can take that incoming http.Request, create an http.Client, and execute the request on behalf of the client. For example:

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, req *http.Request) {

req.RequestURI = ""

removeHopHeaders(req.Header)

if clientIP, _, err := net.SplitHostPort(req.RemoteAddr); err == nil {

req.Header.Add("X-Forwarded-For", clientIP)

}

client := &http.Client{}

resp, err := client.Do(req)

if err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Proxy error", http.StatusBadGateway)

return

}

defer resp.Body.Close()

removeHopHeaders(resp.Header)

for k, vv := range resp.Header {

for _, v := range vv {

w.Header().Add(k, v)

}

}

w.WriteHeader(resp.StatusCode)

io.Copy(w, resp.Body)

}

In this code, req.URL already contains the full target (because the client sent an absolute URI).

We clear req.RequestURI (as required by Go) and then use http.Client to perform the request.

This effectively proxies the request to the destination server.

The example above also strips “hop-by-hop” headers (like Connection) and appends the client’s IP to X-Forwarded-For, mimicking standard proxy behavior.

In practice, the net/http/httputil package provides helpers for hop-by-hop headers, but the key idea is: the Go http.Client does the heavy lifting of making the outbound call.

For HTTPS forwarding, a proxy must also handle the CONNECT method and possibly perform TLS handshakes (for a full transparent proxy or MITM).

Libraries like GoProxy exist to simplify HTTPS proxying, MITM, request modification, etc.

GoProxy’s README describes it as “a library to create a customized HTTP/HTTPS proxy server” which is optimized for traffic and fully programmable.

Depending on your needs, you can either roll your own handler (handling CONNECT for TLS) or leverage a library for advanced features.

Best Practices for Go Proxies

When building or running Go-based proxies, follow these guidelines:

- Use the Standard ReverseProxy for Basic Cases:

For most reverse-proxy needs, the built-inhttputil.NewSingleHostReverseProxyis sufficient.

It’s battle-tested, handles streaming, HTTP/2, and can be customized with hook functions. - Enforce Timeouts:

Never rely onhttp.ListenAndServedefaults in production.

According to Cloudflare’s Go timeouts guide, forgetting to set timeouts can lead to leaked connections and resource exhaustion.

Create anhttp.Serverwith sensibleReadTimeoutandWriteTimeout, or wrap handlers withhttp.TimeoutHandler.

Similarly, configure yourhttp.Transport(used by reverse proxies orhttp.Client) withResponseHeaderTimeoutandIdleConnTimeoutto avoid hanging requests. - Stream and Reuse Connections:

Go’s HTTP transports support connection pooling and streaming by default.

Ensure you deferresp.Body.Close()after proxied calls so connections can be reused.

Avoid reading entire bodies into memory; instead, useio.Copyto stream data back to clients.

This enables high throughput with minimal memory footprint. See High Performance Go for more details. - Manage Headers Carefully:

A proxy should remove hop-by-hop headers (likeConnection,Keep-Alive,Proxy-Connection, etc.) as defined by RFC 2616 §13.5.1.

Thehttputilhandlers usually do this, but if you implement custom proxy logic, be sure to strip or rewrite these headers.

Also, correctly handle theHostheader – usually settingr.Host = target.Host(for reverse proxies) or preservingreq.Host(for forward proxies) as needed. - Preserve Client Info:

Insert or append toX-Forwarded-Foror similar headers so backends know the original client IP. This is crucial for logging, rate-limiting, and geo-location. - Scale Proxies Out:

Don’t assume one proxy will handle all traffic.

For high availability, run multiple proxy instances (possibly in containers or VMs) behind a load balancer.

Ensure health checks (pings to/healthz) are in place so traffic is only sent to healthy nodes. See NGINX Plus health checks for patterns you can adapt.

Summary of Forward vs. Reverse Proxies

| Feature | Forward Proxy | Reverse Proxy |

|---|---|---|

| Direction | Client-to-Internet | Internet-to-Server |

| User | Configured by client (e.g. browser) | Deployed by server/system administrators |

| Common Uses | Bypass blocks, client anonymity, corporate filtering | Load balancing, SSL termination, web acceleration |

| Enhancements | Caching, content filtering | Caching, compression, authentication |

| Examples | Squid, corporate proxies, browser proxy settings | NGINX, Envoy, AWS ALB/ELB, API Gateways |

TL;DR:

A proxy intercepts HTTP requests between client and server, enabling load balancing, caching, security, logging, and more.

It can hide or enforce details of the network.

In Go, the standard library’s net/http/httputil makes it easy to set up a reverse proxy in just a few lines.

For a forward proxy, use http.Client to relay requests to their target. Always apply best practices like timeouts and header handling for a robust proxy.

With these building blocks, you can craft custom proxies in Go for microservices, DevOps tools, or network middleware, gaining fine-grained control over traffic.

Hi there! I'm Maneshwar. Currently, I’m building a private AI code review tool that runs on your LLM key (OpenAI, Gemini, etc.) with flat, no-seat pricing — designed for small teams.

LiveReview helps you get great feedback on your PR/MR in a few minutes.

Saves hours on every PR by giving fast, automated first-pass reviews. Helps both junior/senior engineers to go faster.

If you're tired of waiting for your peer to review your code or are not confident that they'll provide valid feedback, here's LiveReview for you.