Designing a Go ETL Pipeline When SQLite Allows Only One Writer at a Time

At scale, ETL is no longer just extract → transform → load.

It becomes a systems problem.

You’re ingesting thousands of assets, transforming them aggressively, and trying to persist results fast enough that storage doesn’t collapse under contention.

When SQLite is your storage layer, this tension becomes impossible to ignore, because SQLite has a hard rule:

SQLite allows many readers and a single active writer transaction at any given time.

This article walks through how I designed a simple ETL pipeline for large SVG datasets that:

- Fully saturates CPU cores during extraction and transformation

- Respects SQLite’s single-writer constraint

- Avoids lock contention, retries, and throughput collapse

The key was treating SQLite as a serialized sink, not a concurrent participant.

This article is for you if:

- You are new to ETL pipelines

- You are comfortable with basic Go and goroutines

- You are using SQLite for small-to-medium datasets

The Naive Approach Most People Try First

The first instinct is simple:

“I’ll spin up goroutines and let each one write to SQLite.”

This feels correct because:

- Goroutines are cheap

- SQLite is fast

- Parallelism usually helps

Unfortunately, this intuition is wrong for SQLite.

Where Things Break

The workload looks simple on paper:

- Scan large SVG datasets

- Parse each file

- Extract metadata

- Convert SVG → base64

- Persist structured metadata into SQLite

But under load, naive parallelism fails fast.

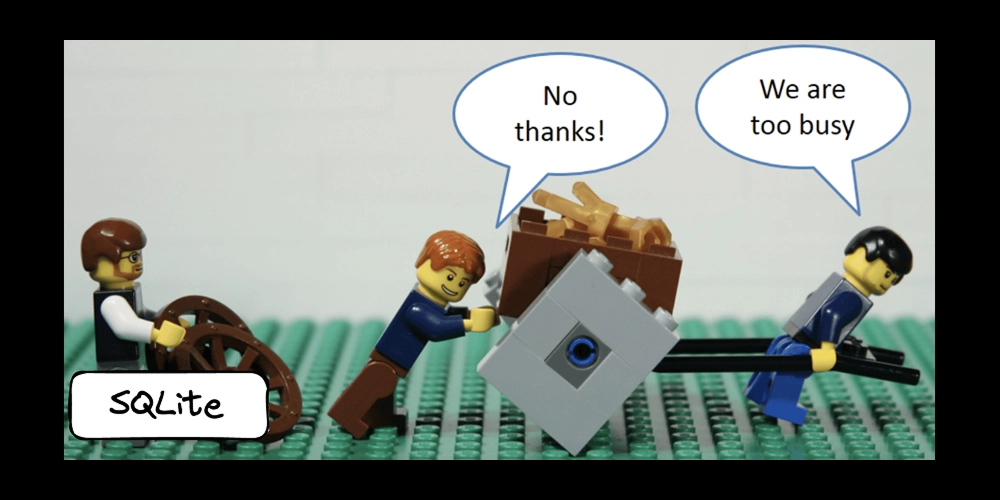

SQLite offers excellent transactional guarantees and is incredibly fast when used correctly, but it does not scale with concurrent writers.

If every goroutine attempts inserts directly:

- Writes are serialized anyway

- Lock contention explodes

- SQLITE_BUSY errors begin to surface

- In poorly structured code paths, this may later cascade into SQLITE_LOCKED

- Throughput drops sharply

Under concurrent writers, SQLite does not fail because the database is "broken", but because it is busy.

SQLITE_BUSY indicates contention between multiple database connections

attempting to write at the same time.

In contrast, SQLITE_LOCKED usually signals an internal conflict within the same connection (or shared-cache usage), and is often a followup symptom of poorly structured concurrency rather than the root cause.

Reframing the Pipeline

Instead of parallelizing everything, the pipeline must respect what scales and what doesn’t.

- Extract & Transform → CPU-bound → scales with cores

- Load (SQLite writes) → serialized → must remain linear

That insight drives the entire architecture.

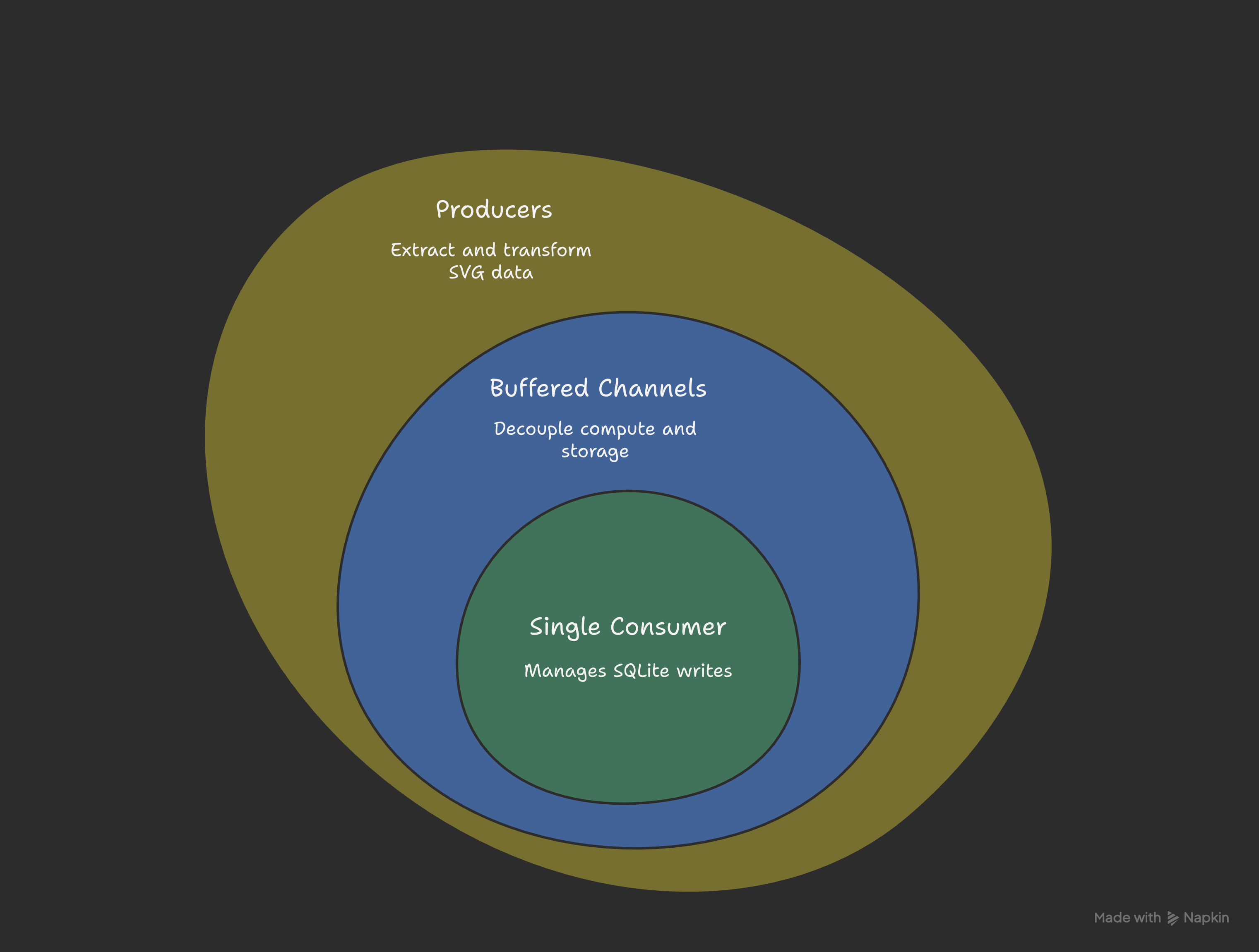

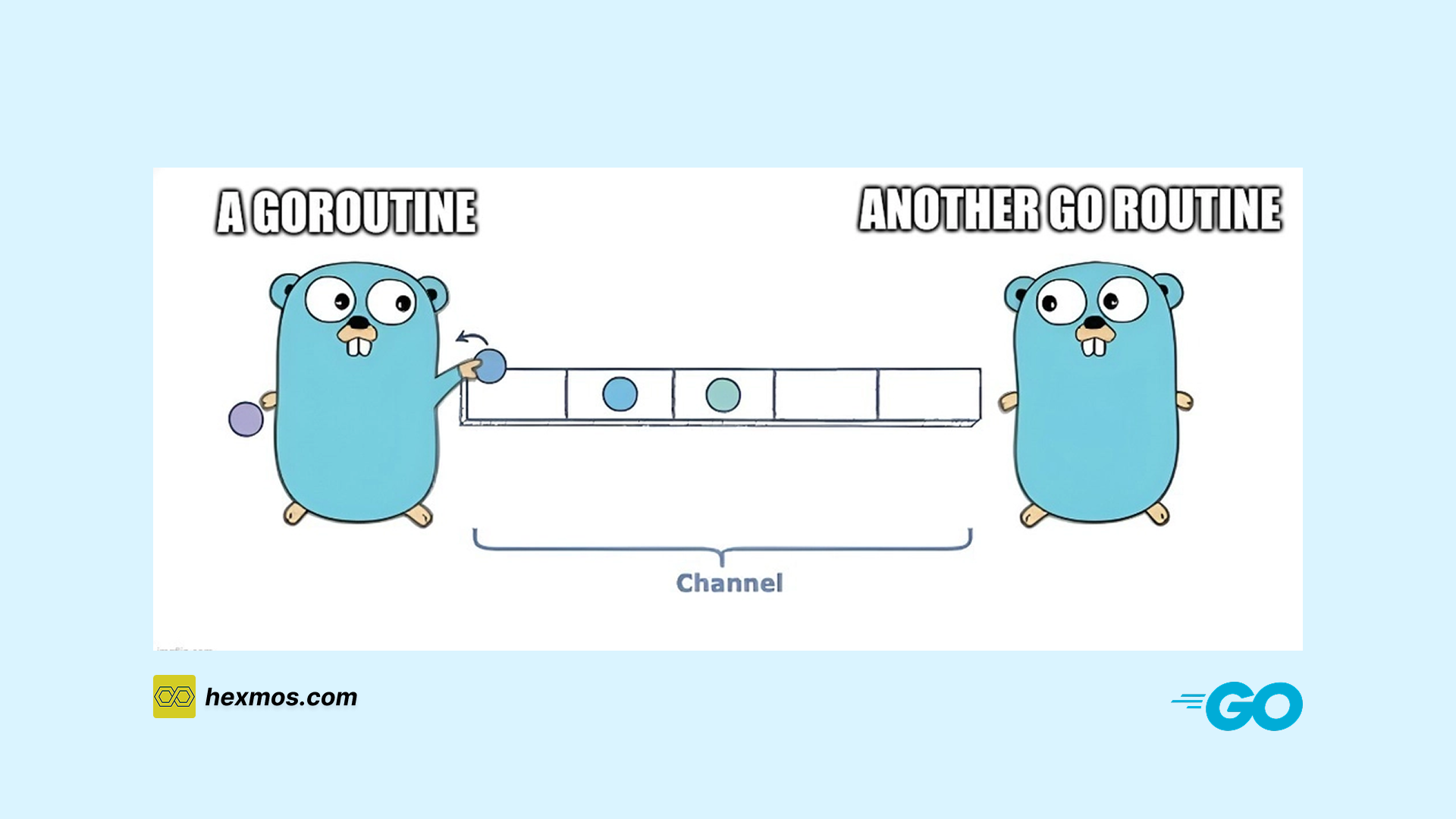

Architecture Overview

The ETL pipeline is split into three explicit stages:

- Producers (Extract + Transform)

Parallel goroutines performing all CPU-heavy SVG processing. - Buffered Channels (Pipeline)

Decouple compute from storage and apply backpressure. - Single Consumer (Load)

A dedicated goroutine that exclusively owns SQLite writes.

The goal is simple:

Max out CPU usage without ever letting SQLite experience write contention.

Why This Architecture Works at Scale

On my machine:

- 8 CPU cores

- 7 cores dedicated to producers:

- SVG parsing

- Base64 encoding

- Metadata extraction

- Insert payload preparation

- 1 dedicated goroutine exclusively owning SQLite writes

This achieves maximum parallelism where it matters, with a stable and explicit write bottleneck

SQLite stays fast because it is never stressed beyond its design.

Components in Detail

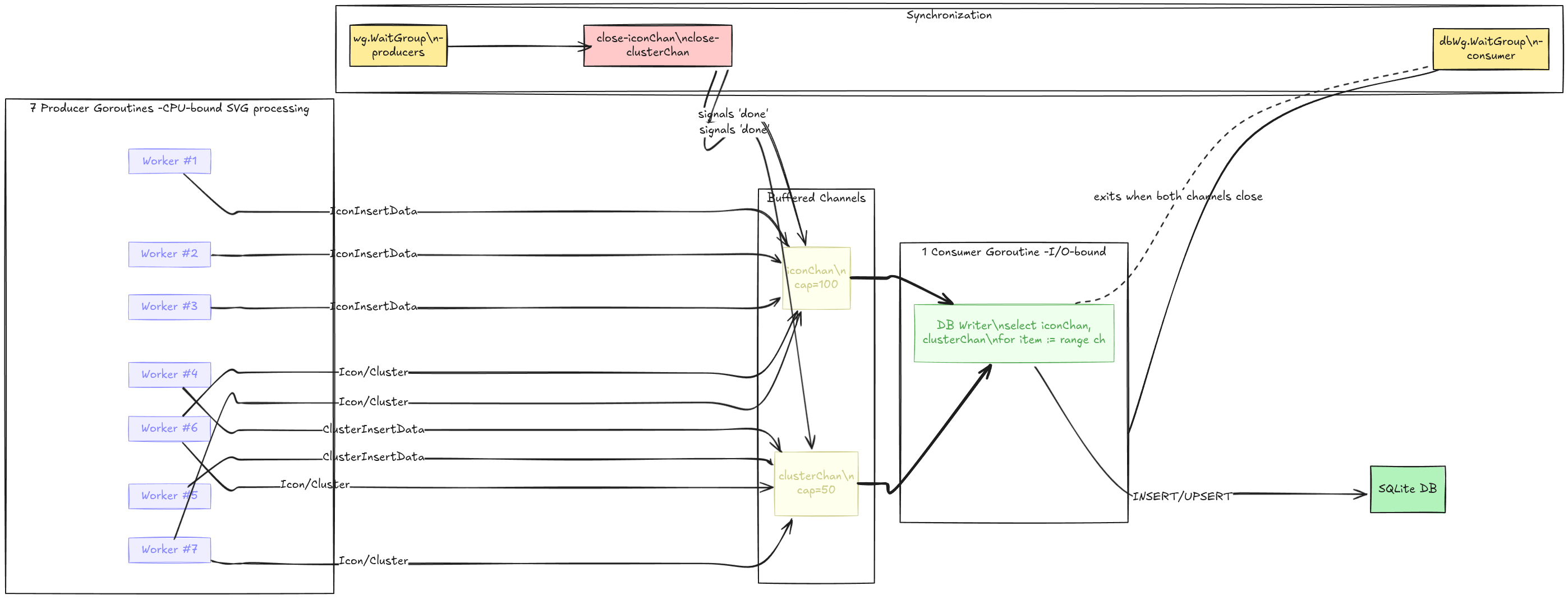

1. Buffered Channels (ETL Pipeline)

Two buffered channels represent the handoff between transform and load:

iconChan→ icon metadataclusterChan→ cluster metadata

iconChan := make(chan IconInsertData, 100)

clusterChan := make(chan ClusterInsertData, 50)

These buffers are critical:

- Producers continue working until buffers fill

- Consumers drain at SQLite’s pace

- Backpressure naturally forms without locks or sleeps

This is the ETL boundary.

2. Producer Goroutines (Extract + Transform)

Seven workers run concurrently. Each worker:

- Pulls category jobs from a queue

- Reads SVG files

- Parses and transforms content

- Emits ready-to-insert payloads

for id := 0; id < maxWorkers; id++ {

wg.Go(func() {

for cat := range categoryChan {

// CPU-heavy SVG processing

iconChan <- IconInsertData{ /*...*/ }

clusterChan <- ClusterInsertData{ /*...*/ }

}

})

}

Important detail:

- No database calls happen here

- Producers are pure compute

- This stage scales linearly with CPU cores

At scale, this separation is non-negotiable.

3. Single Consumer Goroutine (Load)

SQLite does not tolerate concurrent writes, so all database access is owned by a single goroutine.

Instead of letting workers write directly, the pipeline funnels all

write-ready payloads into a single consumer that:

- Reads from multiple channels

- Executes inserts sequentially

- Owns the SQLite connection for its entire lifetime

go func() {

defer dbWg.Done()

for iconChan != nil || clusterChan != nil {

select {

case iconData, ok := <-iconChan:

if !ok {

iconChan = nil

continue

}

// Insert iconData into SQLite

case clusterData, ok := <-clusterChan:

if !ok {

clusterChan = nil

continue

}

// Insert clusterData into SQLite

}

}

}()

This goroutine is the only place in the entire program that touches SQLite.

Why this matters:

- Channels stay independent

- SQLite ownership is undeniable

- No transactional conflicts

- No lock retries

- Writes remain fast and predictable

- One goroutine owns SQLite for its entire lifetime

Why This Pattern Fits SQLite Perfectly

SQLite’s model is simple:

One write transaction at a time.

If you ignore that:

- Parallel writers just fight

- SQLite serializes anyway

- Performance gets worse, not better

By designating explicit write ownership:

- Serialization becomes intentional, not accidental

- Throughput increases

- Failure modes disappear

Producers never block on the database.

SQLite never blocks producers.

Performance Characteristics

CPU Utilization

Seven producer goroutines keep seven cores saturated during heavy SVG processing.

Database Stability

SQLite runs with low CPU usage and zero lock contention.

Throughput

High ingestion rates are sustained because:

- Producers never wait on SQLite

- Consumers never contend

- Channel buffers absorb burstiness during crawling

Throughput scales until the SQLite writer becomes the dominant bottleneck, at which point the system remains stable instead of collapsing.

Final Notes

This is not a workaround, it’s a correct mental model for embedded databases. ETL performance is not about “more goroutines”.

It’s about:

- Knowing where parallelism helps

- Knowing where it hurts

- Designing boundaries explicitly

SQLite isn’t slow. Unstructured concurrency is.

What Not To Do

- Do not open SQLite connections inside worker goroutines

- Do not retry failed writes aggressively

- Do not increase busy_timeout and hope it fixes contention